A New Strategy for a New Food Landscape.

I know, I know. I told you to ditch food categories like "Carbs, Protein, and Fat" in favor of categories like "Good Soil", "Healthy Animal", and "Freshly Picked". And I meant it.

But then, I got a bunch of questions about carbohydrates after I posted, Fix Your Insulin; Fix Your Fat. That post must have hit a nerve, because the short version spread to 4,758 people on Facebook in a few hours.

You asked me for some practical carbohydrate guidelines to keep your blood sugar and insulin within healthy range.

Wonderful. Let's dig in.

So What's All the Fuss about Carbs?

Carbs have been a flash point for years, both among carb-restricted dieters and among the carb-centric diet dictocrats at the USDA. So, naturally you can find low-carb and high-carb diets out there, both claiming to tell you the whole truth and nothing but the truth—not about food—but about this abstraction called carbohydrates. (As if carbs mattered more than food somehow.) It can feel more like a courtroom drama than a genuine omnivore's dilemma. The either/or tension often leaves us feeling confused. And it should.

Because of course, the whole debate about whether carbs are "in" or "out", is artificial. Carbohydrates cannot be all good, as Sugar Science clearly shows us, but neither can they be all bad, because veggies are carbohydrates too.

Obviously then, it's not about getting a carbohydrate divorce; it's about choosing your carbohydrate source.

But that's easier said than done. Because the food landscape has changed. Dramatically.

Why Your Ancestors Had Fewer Choices but More Freedom.

We're a choosy bunch, humans. And our choosiness was there before any republic, or commonwealth, or democracy gave us permission. For as far back as we have anthropological data, we have been choosy omnivores, with highly developed sensory organs to help steer us toward fresh, nutrient-dense foods, and away from rotten food, or away from food that isn't food at all, like tree bark or gravel.

This intuitive approach to eating worked fine for generations, until industrial "food science" hijacked our senses with highly palatable food-like substances that neither our great-grandmothers, nor our ancient genome had ever seen before. As we began to forage for carbs in the supermarket instead of the berry patch, it became increasingly difficult for us to distinguish between nutrient-dense foods and nutrient-poor foods, or “food” that wasn’t food at all.

The supermarket shelves are now so full of bloat, that it really does feel like we need blogs and experts to help us find our way—to navigate a glittering food landscape that is, relatively speaking, entirely new to our species.

When I first realized this, I got angry, then depressed. Then, something shifted inside me. My self-respect kicked in.

Because in a sense, nothing has changed. We still have the privilege and responsibility of judging carbohydrate foods one at a time, as we always did. It's just that now, since we live in a science experiment, we have to do things a little more scientifically (either that, or get out of the experiment).

So the goal of this post is to enhance our decision-making capacity in the trenches. To lay down a framework that gives us the dignity of natural choice in an unnatural environment, again. Call me an optimist, but I believe we can recover our instincts by educating them.

Managing Your Blood Sugar Before It Manages You.

Let’s start by making a useful distinction: Simple Carbs vs. Complex Carbs.

Simple carbs are just that, simple. They are just a few sugar molecules strung together, like beads on a string. Or they are even simpler than that: a single molecule of glucose. Glucose is as simple as it gets as far as the body is concerned. When we say "blood sugar", we mean blood glucose.

Complex carbs on the other hand, consist of many, many, many sugar molecules strung together into many, many strings that branch and bind together. If a simple carb is a length of rope with a few knots in it, then a complex carb is an entire obstacle course of rope nets with Gordian knots. Which one do you think would take longer to untie? Silly question.

No surprise then, it takes your body a lot more time to digest, or “untie”, complex carbs than it does simple carbs. And this is what makes all the difference in how you feel when you eat one or the other.

So let’s eat some simple carbs and see what happens.

You’re hungry. Famished. You sniff out some quick energy, some cereal, syrup, candy, bread, pasta, cakes, cookies, or muffins. Your ancient genome comes alive and says “Wow. Awesome. Easy carbs! Let’s chow down and get fat before winter, before this stuff dies and I’m stuck with salted herring."

You eat. As expected, digestion is a cinch, and all that sugar hits your blood stream at once. It’s fuel injection, baby. No slow infusion here, no sissy soak in some ninny nutrient broth. This is electrifying. This is neon. This is Vegas and you just hit the jackpot.

A big alarm goes off. Because even though you can burn sugar for fuel, high levels of blood sugar are toxic to your most delicate structures, like red blood cells and nerves. (Your body has always been nervous about too much of anything, even oxygen.)

The sugar bomb needs to be diffused and cleared ASAP. And it looks like it’s going to be a big job. So, rather than releasing a tincture of insulin to take care of a trickle of carbs, your pancreas convulses and releases a tsunami of insulin to sweep aside the high tide of sugar. It’s a little violent, but effective. Often too effective.

Big surges of insulin cause at least two problems: First, they tend to overcorrect your blood sugar and drive it paradoxically low, so you experience the all-too-familiar energy crash associated with eating sugar (what goes up, must come down)—you feel moody, jittery, and ravenous for simple carbs right now, all over again, a mere 90 minutes or so after noshing on that “energy bar”. And second, high insulin levels can have a “threshold effect”, unlocking fat depots to receive sugar for storage, instead of escorting it mostly into muscles and mitochondria to be burned.

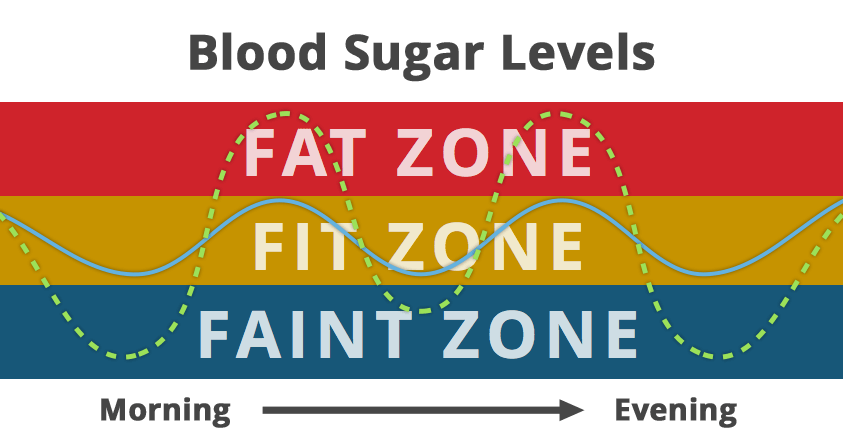

For most of us, the blood-sugar roller coaster starts with a bowl of cereal for breakfast and a cold glass of OJ. From there, we start doing the wave, rocketing up and down through three main blood sugar zones in rapid succession. I call these zones: the Fat Zone, the Fit Zone, and the Faint Zone.

My names aren’t very subtle, are they? Because obviously, we want to spend most of our time in the Fit Zone. Is there anything that can help us? Yes. Complex carbs. (And fat and protein too, by the way, yum).

Complex carbs generally have what is called a low glycemic load, which simply means that the modest amounts of sugar and starch they contain will absorb slowly, offering you more sustained energy, better weight control, better mood and energy control, and better overall health.

Actually, there is a whole list of benefits to complex carbs:

- Fiber

- Satiety & Fewer Cravings

- Sustained Energy

- Sweep Toxins from the Gut

- Stabilize Blood Sugar & Insulin

- Rich in Vitamins, Minerals, Enzymes, & Phytonutrients

- Help Prevent Chronic Disease

- Stimulate Metabolism & Promote Fat Loss

The Good, the Not Too Bad, and the Ugly.

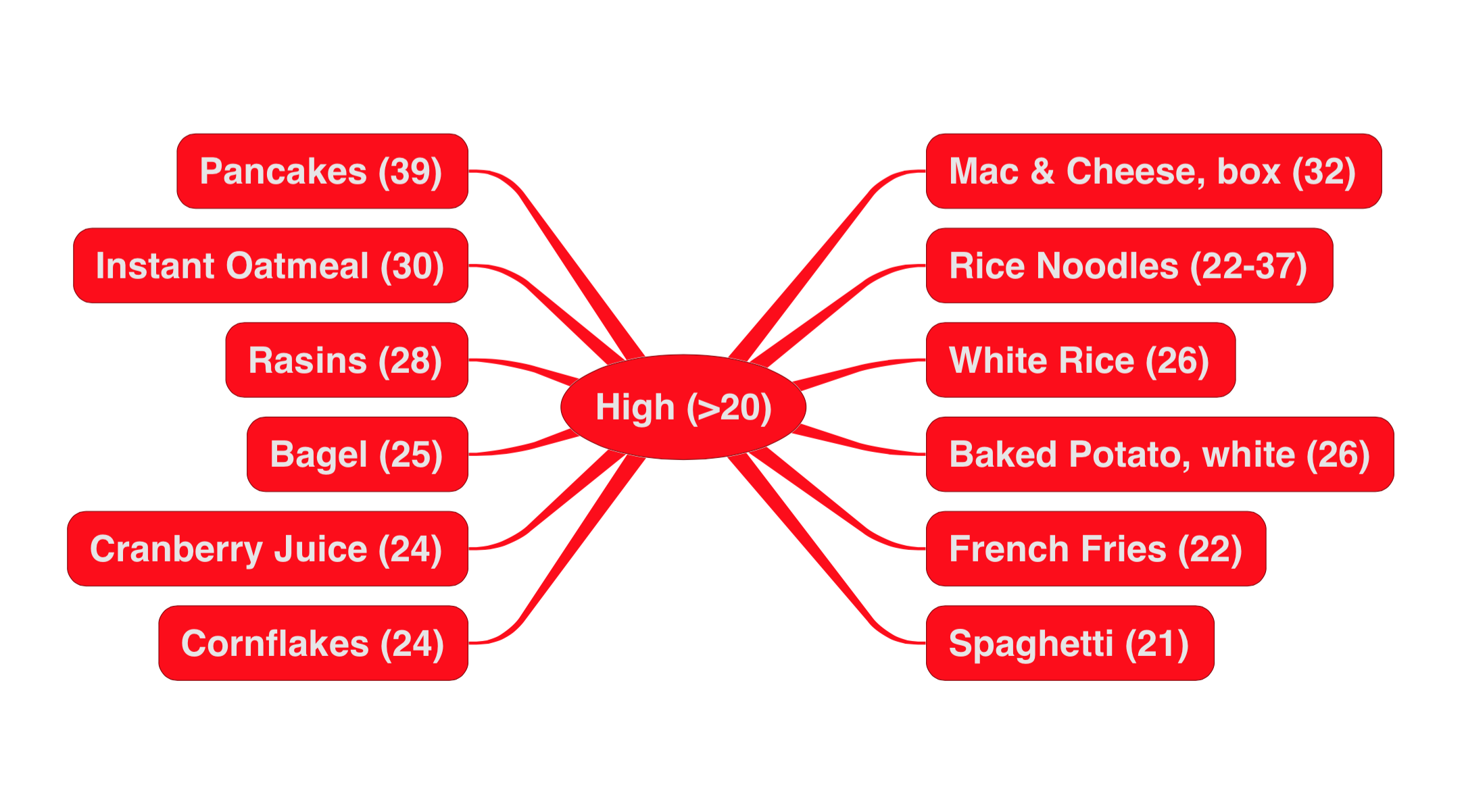

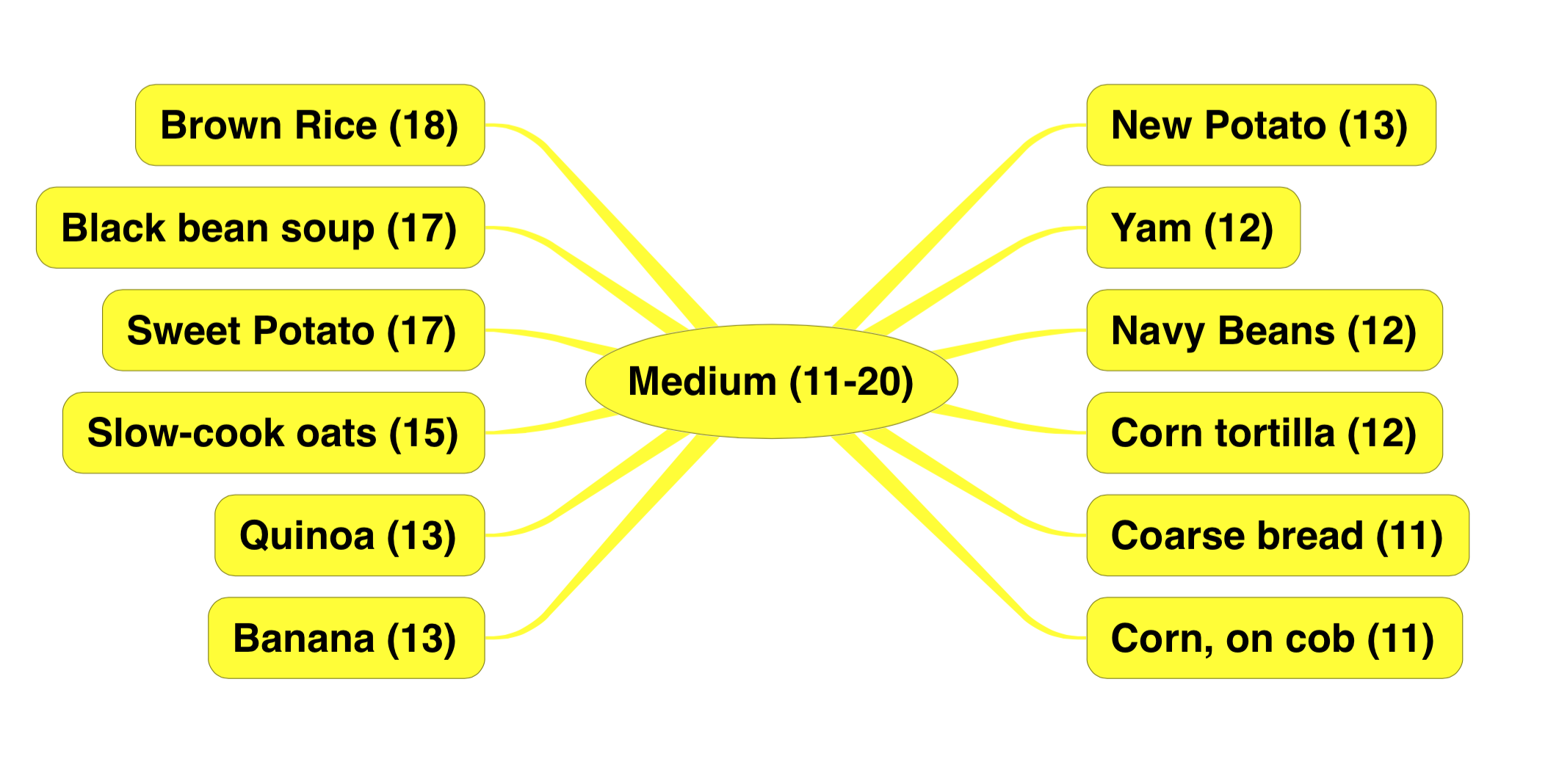

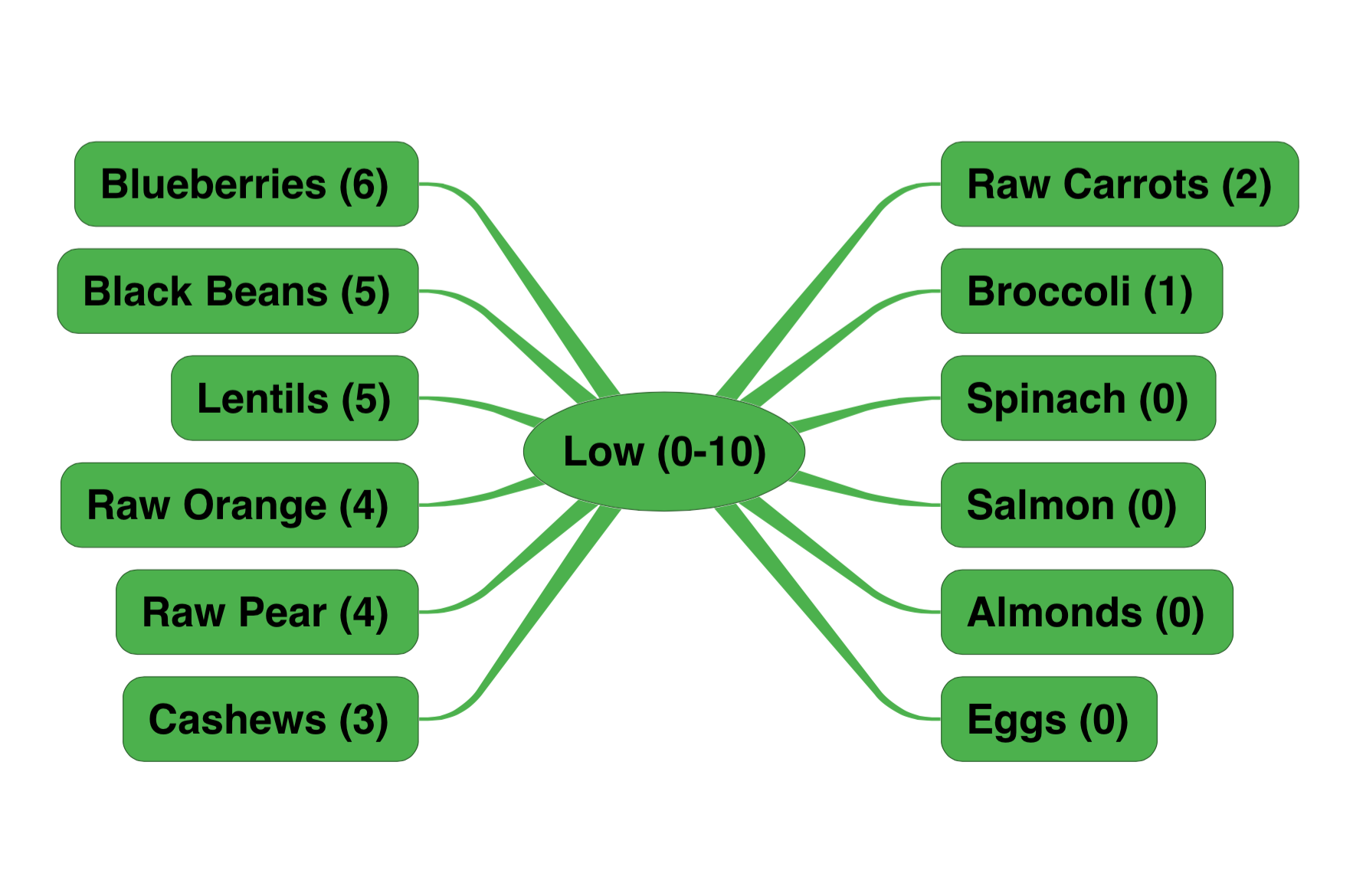

It turns out we can vet just about any carbohydrate source in terms of its Glycemic Load (GL). Yay science. There’s a scoring system (isn’t there always), in which foods are ranked low, medium, or high depending on their glycemic load. They are assigned a number which takes into account both the rate and amount of sugar absorbed on average per serving: 0-10 (low), 11-20 (medium), >20 (high).

Anything between 0-10 offers a low glycemic load that will keep your blood sugar nicely centered in the "Fit Zone”. Foods with a glycemic load from 10-20 may push your system a little harder. And foods scoring greater than 20 are in the red zone.

Below are some examples of Low, Medium, and High Glycemic Load foods. (Not all of them are carbs, because I want to give you a feel for how proteins and fats compare as well.)

My big giant hope is this:

After examining these charts and experimenting with them a little, I'd like to see you experience some intuitive food freedom in your life. I’d like to see you be able to guess how any food would stack up in this rating system, without having to google it. Because I admit, when I first encountered this system I was a little put off. I was like “seriously, numbers?". But after a little practice I found I was indeed able to recognize low-glycemic load foods better for having used it. I was then able to drop the numbers and judge foods by their look and feel and relationship to other foods. This is what I mean by educating your instincts.

High Glycemic Load Graph (>20).

High Glycemic Load in List Form:

- Pancakes - 39

- Mac & Cheese, boxed - 32

- Instant Oatmeal - 30

- Raisins - 28

- Rice Noodles - 22-37

- Baked Potato (white) - 26

- White Rice - 26

- Bagel - 25

- Cornflakes - 24

- Cranberry Juice Cocktail - 24

- French Fries - 22

- Spaghetti - 21

Medium Glycemic Load Graph (11-20).

Medium Glycemic Load in List Form:

- Brown rice - 18

- Black bean soup - 17

- Sweet Potato - 17

- Slow-cook oatmeal - 15

- Quinoa - 13

- Banana - 13

- New Potato - 13

- Yam - 12

- Navy Beans - 12

- Corn tortilla - 12

- Coarse whole grain bread - 11

- Corn on the cob - 11

Low Glycemic Load Graph (0-10).

Low Glycemic Load in List Form:

- Blueberries - 6

- Black Beans, (whole) - 5

- Lentils - 5

- Raw Orange - 4

- Raw Pear - 4

- Cashews - 3

- Raw Carrots - 2

- Broccoli - 1

- Spinach - 0

- Salmon - 0

- Almonds - 0

- Eggs - 0

You'll notice that pureeing black beans into soup increases their glycemic load compared to eating them whole. That's a transferable concept: any milling, cooking, or preparation technique that makes carbohydrates quick-to-digest will increase their glycemic load. Basically, the more you have to chew your carbs, the better.

Translation?

I fill 2/3 of my dinner plate with non-starchy veggies, mostly leafy greens. They are complex, slow-to-digest, and easy on the insulin. I don't choose these veggies chiefly because I'm looking for low-glycemic carbs, though. Truth be told, I'm looking to maximize nutrient density (the ratio of nutrients to calories). And there's nothing like non-starchy veggies for vitamins, minerals, enzymes, and phytonutrients. But the fact that they are also low-glycemic is a double bonus. I'll take it.

The other 1/3 of my plate is generally some jumble of quality protein, fat, and medium GL starch. I really like thinking in terms of big visuals like this and plate ratios because honestly, I don’t like numbers; I like geometry. And I like food.

Wrapping Up.

I hope you don’t find any of this austere or obscure. But if you do, consider this:

There's nothing wrong with an occasional high-glycemic indulgence now and then--but ever since the introduction of industrial foods, the indulgence has become anything but occasional. With added sugar in 74% of packaged foods, the splurge is now unremitting and unwitting. No wonder the average consumption of sugar is 150 pounds per person per year! It's the new normal. And that's just sugar, to say nothing of the steady stream of other simple carbs.

So here's my recommendation if you want to take control of your health: look at all the wonderful stuff you can eat (rather than the few items you can’t eat). That way, austerity becomes all about abundance. Or think of it as a return to the constraints and freedoms of your ancestors, which you are so totally optimized for. Whatever works for you, give it a try. Be mindful of your carbs. Manage them before they manage you. Take delight in whole foods that crunch and gush and make you chew. And just feel good again.

Yours in Health and Resilience,

Marc Wagner, MD

P.S. A good source for newbies, with more definitions such as the difference between Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load is Diet Database. It also has extended PDFs from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition: International Table of Glycemic Index and Load, which I used to gather the specific Glycemic Load numbers for foods in this post.

What to read next:

- Grow Your Bugs, Not Your Belly. Does Having a Small Microbiome Give You a Big Gut?

Cover Image: "No Evil", by Geoffery Fairchild on Flickr.