Why Saturated Fat Isn't All Bad...and Why Vegetable Oil Isn't All Good.

It's easier for the world to accept a simple lie than a complex truth. - Tocqueville

I once had a registered dietician ask me, "Isn't coconut oil just saturated fat?" She was biting her tongue. You could tell she really wanted to uncork and say something like: "Isn't coconut oil one of those naughty, nasty fats you should be telling people to avoid!?"

If an RD has this question, I'm sure you do too. So let's take a look at it.

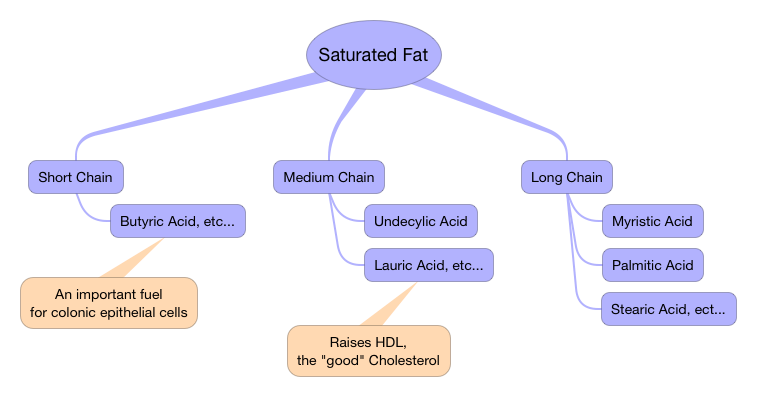

First, understand that saturated fat is a generic term. It's a category, not a compound. It describes a whole family of fats. And, as anybody with a large family will tell you, the cast of characters can get, ahem, very diverse.

How diverse?

Well, underneath our category "saturated fat", lie three more categories:

- Short chain fatty acids.

- Medium chain fatty acids.

- Long chain fatty acids.

Within these subcategories bloom an assortment of compounds, like lauric acid, myristic acid, and palmitic acid. And like the branches of a tree, these compounds vary widely in length, ranging from tiny 2-carbon snippets to expansive 36-carbon freight trains, and everything in between.

There are 35 unique saturated fats in all. Some of them are downright good for you; others not so much, depending on your genetics and inflammatory status. All of them need to be balanced with other fatty acids and other foods.

It's beautifully complex. It's biology.

Fortunately, eating with common sense is NOT complex and it's always beautiful, as long you don't villainize an entire category of nutrients along the way.

So how exactly did our notions of saturated fat become so shallow?

Well, that too, is a complex story. But I'll cut to the chase.

For a long time now, our most trusted sources of nutritional information have been hypnotized by The Lipid Hypothesis--the idea that fat is bad and that saturated fat is really really bad.

This idea stems partly from the unquestioned belief that fat makes you fat (which it doesn't necessarily), and partly from the observation that certain kinds of saturated fat may raise cholesterol. And since we all "know" that cholesterol is bad, we have waged war against its proximate cause, saturated fat, for 30 years without mercy--or nuance.

Since the 1970's this message has gone out like a siren song from agencies no less esteemed than the Food and Drug Administration, the World Health Organization, the International College of Nutrition, the United States Department of Health and Human Services, the American Dietetic Association, and the American Heart Association. There are complex reasons for such a simplistic message, reasons that have as much to do with an agricultural policy that subsidizes corn and soy and vegetable oils, as it does with good science. But that's a discussion for another post.

I'm not suggesting it's time to canonize saturated fat, but it is time to stop villainizing it. As research continues to accumulate failing to link all saturated fats to heart disease, I think it's becoming clear, we do not need to throw the baby out with the fat water.

In fact, it turns out there is something special about the kind of saturated fat in coconut oil--as we shall see.

The Benefits of Short & Medium Chain Saturated Fats.

As I said, saturated fats come in various lengths: short, medium, and long. Coconut oil is interesting because it contains an especially large proportion of medium chain fatty acids. Chief among these is lauric acid, which it turns out, is a saturated fat that raises blood levels of HDL, the "good" cholesterol.

Wait, what?

Yes you read that right. We're talking about a saturated fat that actually improves your blood cholesterol profile. Do you see why nuance is important? It's seldom that we can go around making blanket statements about anything, even saturated fat.

Franken Fats, Biochemistry, and Things that Go "Boing".

There's another nuance I think you should know about. But it requires a crash course in biochemistry. (I know, I just said the "B" word. But you can do this. I'll make it easy.)

Have you ever wondered what the difference really is between a saturated fat and an unsaturated fat and why it even makes a difference?

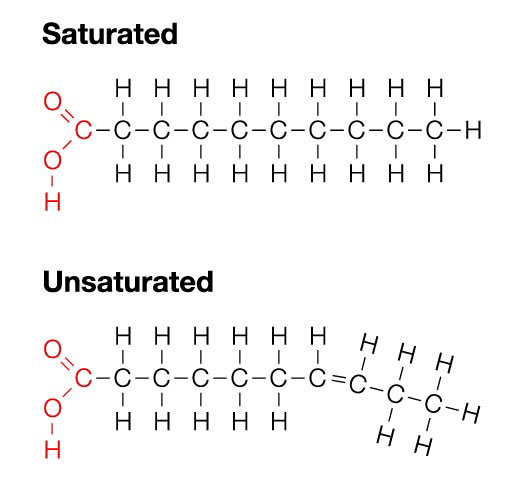

Think of fatty acids as strings of carbon atoms, joined together like little boxcars. They make a sort of train.

Now take your fat and magnify it. (Did I just say that?) You see that each boxcar, each carbon atom, has several arms sticking out of it. These little arms are where hydrogen atoms may attach if they want to. When all the docking arms are full of hydrogen, the fat is said to be saturated, because, well, it's full. Like a sponge full of water, it can't take anymore. Conversely, a fat is said to be unsaturated when some of its arms are still "empty" of hydrogen.

But these "empty" arms don't stay empty. They don't just flutter in the breeze. Instead, they swing into line and form a double bond with the next boxcar.

In real life, this would cause a spectacular train wreck. But let's pretend our boxcars are made of Play-Doh; they can bend around freely and form double bonds, like a yoga teacher touching her toes.

In this case, instead of a straight train, you would have a bendy train, with lots of kinks in it. And this is exactly what an unsaturated fat looks like--kinky. Think of kinky hair.

And just like kinky hair, an unsaturated fat won't lie flat.

Fats that won't lie flat are fats that won't stack neatly together, like a pile of odd-sized wood. They keep rolling off each other; they keep flowing. So they are liquid--even when cold.

The advantage of an unsaturated fat is that it is loose and supple in your body. The disadvantage is that it is unstable and prone to oxidation; it's liable to spring one of its double bonds--boing--and let some oxygen in, which turns the fat rancid, at which point it starts spinning off nasty free radicals that poke holes in your tissues like bullets. And the hotter an unsaturated fat gets, the wilder and more unstable it becomes.

On the other hand, fats that are predominantly saturated, like butter or coconut oil, are "stackable" fats. They are solid at room temperature. This makes them more stable than unsaturated fats and thus less vulnerable to rancidity and the formation of harmful free radicals.

That sounds like a good thing, doesn't it?

It is, especially if you happen to be cooking. Because heating an unsaturated fat is a sure-fire way to speed its oxidation and start forming what I call "franken fats". These are twisted and damaged fats bristling with free radicals.

If you're cooking with significant heat, you WANT an oxidation-resistant saturated fat like butter or coconut oil, NOT an unstable polyunsaturated fat like corn oil, canola oil, sunflower oil, safflower oil, or soybean oil.

I know, I probably just blew the lid off everything you thought was healthy, because you've been told your whole life to avoid butter and cook with vegetable oil. But, there it is. With the exception of olive oil, I personally avoid cooking with typical vegetable oils.

Why Do I Make an Exception for Olive Oil?

Because olive oil is actually not a polyunsaturated vegetable oil, it's a monounsaturated fruit oil. It's only 9%-14% polyunsaturated. The rest of it is monounsaturated (70-77%) and saturated (14%). That's why olive oil gets thick, or semi-solid, in the fridge.

Why is this important?

Because olive oil's primary constituent, oleic acid, has only one double bond, only one place where hot oxygen can squeeze in and distort the molecule into a franken fat. It's basically just one bond away from being a saturated fat.

Even so, the best olive oils (the ones that are extra virgin, unfiltered, and loaded with polyphenols) can only be used at low temperatures anyway. Otherwise, the delicate polyphenols will burn and turn your lovely stainless steel pans green. Olive oil is best for slow sautés and salad dressings, not big heat.

What About Canola Oil?

"Ignorance is bliss...'till you get screwed" - UJ Ramdas

You see a lot of Canola Oil being used these days as a cheap alternative to olive oil, because Canola contains about 60% monounsaturates. But alas, that's where the similarity ends. Not only is most Canola genetically engineered to withstand big doses of herbicide (making it hard on the environment), it also contains about 30% polyunsaturates, making it clearly less stable than olive oil for cooking. But it gets worse. About half of the polyunsaturates in Canola oil are omega 3's, which are the most unstable polyunsaturates of all and SHOULD NEVER be used for frying.

You want to consume your omega 3's fresh and raw if possible. Take a page from the fish and flax oil manufactures. They go to great lengths to keep omega 3's from oxidizing by using instant bottling procedures, vacuum seals, nitrogen displacement, tinted glass, and even lightless containers. And then you're honor-bound to refrigerate the oil after opening. When's the last time you saw Canola Oil treated with that kind of respect? Forget the hype. If Canola oil is a good source of omega 3's, then it cannot also be a good oil to cook with. The Edible Oils Industry can't have it both ways. Don't let them.

Which Brings Us Back to Coconut oil.

So here's the research roundup for you:

-

Coconut flakes were found to have a cholesterol-lowering effect in subjects with high cholesterol levels.

-

A high intake of coconut in Indonesians was not associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

-

When studying heart disease in women, intakes of SCFAs and MCFAs were not significantly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease.

-

No specific role for coconut oil was found in the causation of cardiovascular disease in a study in India.

-

Medium Chain Fatty Acids may help promote weight maintenance without raising "bad" cholesterol levels.

-

Coconut milk contains a large proportion of lauric acid, a saturated fat that raises blood levels of HDL, the "good" cholesterol.

-

Medium Chain Fatty Acids have specialized nutritional and metabolic effects, including being readily digestible and passively absorbed making them of particular interest for neonatal nutrition.

-

As early as the 1960s, high dietary supplementation of Medium Chain Fatty Acids was linked to potential antimicrobial regulation of gastric microbes.

Okay. Impressive. At least one saturated fat is back on the menu.

(Note: Please don't confuse coconut oil with palm kernel oil. I know they both make you think of palm trees, but their fatty acid profiles are different. Palm kernel oil is not associated with the health benefits of coconut oil.)

Let's Summarize.

There are only 5 key points you need to remember:

-

Saturated fat is a category, not a compound. The varying chain lengths of saturated fats have different effects on our bodies.

-

Long Chain Fatty Acids generally have a negative effect on cardiovascular risk parameters--if you assume cholesterol is the enemy. (Inflammation may turn out to be the real enemy).

-

Short Chain Fatty Acids and Medium Chain Fatty Acids have important positive effects ranging from improved gastrointestinal health, to improved weight management, to improved HDL (the "good" cholesterol).

-

Coconut oil happens to be rich in beneficial short and medium chain fatty acids, especially Lauric acid, a medium chain fatty acid that accounts for nearly 50% of all the fat in coconut oil.

-

Coconut oil is relatively heat stable. It is a fantastic cooking fat below its smoke point (350 degrees).

And Let's Bring it Home.

There you have it. A little B-chem, a little fun, and a big oil change.

You may be wondering which coconut oil I use. I don't mind telling you. My wife buys Nutiva Organic Extra Virgin Coconut Oil. It's the bomb: cold pressed, not refined or deodorized or bleached in any way, and of course it's made without pesticides, hexane, or GMO's. The taste is fairly neutral and even more neutral if you add salt. Not only do we use it for cooking, but I've been caught shaving with it once or twice. Baby soft.

Yours in Health and Resilience,

Marc A. Wagner, M.D., M.P.H

What to read next:

- My Best Fat Friend for Life. The Case for Olive Oil.

References:

-

Trinidad TP, Loyola AS, Mallillin AC, et al. The cholesterol-lowering effect of coconut flakes in humans with moderately raised serum cholesterol. J Med Food. 2004;7(2):136-140.

-

Lipoeto NI, Agus Z, Oenzil F, Wahlqvist M, Wattanapenpaiboon N. Dietary intake and the risk of coronary heart disease among the coconut-consuming Minangkabau in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13(4):377-384.

-

Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Dietary saturated fats and their food sources in relation to the risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(6):1001-1008.

-

Kumar PD. The role of coconut and coconut oil in coronary heart disease in Kerala, South India. Trop Doct. 1997;27(4):215-217.

-

Physiologic Effects of Medium-Chain Triglycerides: Potential Agents in the Prevention of Obesity. J. Nutr. 132 (3): 329–332. 1 March 2002.

-

Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester AD, Katan MB (May 2003). "Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on the serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials". Am J Clin Nutr, 77 (5): 1146-55

-

Sheila K. Jacobi and Jack Odle. Nutritional Factors Influencing Intestinal Health of the Neonate. Adv Nutr September 2012 Adv Nutr vol. 3: 687-696, 2012