The Making of the Modern Diet.

Sooner or later everyone sits down to a banquet of consequences. —Robert Louis Stevenson.

The year is 1992. A friend of mine, David, is looking for a roommate. He has this little house near the university with two small bedrooms and a full kitchen. He needs someone to split the rent. The price is right. And I'm tired of dorm life. So I volunteer (before anyone else gets wind of the offer).

"Can you cook," David asks? "We'll be sharing that responsibility."

"Sure. No problem," I say, thinking of Ramen and Taco Bell takeout. How hard could it be?

Deal.

We get settled and I draw the short straw. It looks like I will be christening the kitchen.

"No worries," I tell myself. "I got this." My secret Ramen recipe (wait for it): crumbled noodles, boiling water, and tabasco sauce. We're in business. Ta da!

David eats politely.

After classes the next day, I stroll up to the house and falter. A cripplingly delicious smell is seeping from around the weather stripping at the front door; I can feel something like an aromatic grappling hook coming for me. Without warning, waves of hunger and sentiment wash over me; it smells like home, mom, Thanksgiving, Christmas; there's a feeling of letting down and letting go, coming in out of the rain. In a whiff, I go from being a dorito-bag bachelor to a weak-kneed little boy. Lordy. My roommate is making baked salmon, baked salmon!, and Esau's Pottage (a hearty stew of lentils and rice), with a little side salad and vinaigrette. I am undone.

I sit down and eat, snuffling like a lost animal.

Halfway through my second plate, I think, "Okay. I need to up my game. Maybe it's time to grow up—stop being an adult Gerber baby—learn to cook some real food already. Could I do that?"

So I make a deal with David: if he cooks the same thing again tomorrow night, I will watch and learn. We both win. No more Ramen for either of us.

He agrees. And the rest is history.

23 years later, David and I still keep in touch. The subject of food comes up regularly. We have our preferences and intolerances, but there's one thing we always agree on: real food is worth it.

Back to the Future.

So how is it that an educated person like me, in his third decade of life, could have come to think of Top Ramen as a real meal? How did this happen? How does any one of us ever get to the place where we think of food as just fuel with interchangeable parts—carbs, protein, fat—as if it were some modular system of edible legos..."after all, parts is parts, ain't it"?

It is my hope that in a few minutes, you'll glimpse something that could change your life: a brief history of the modern diet. It's brief, because it's brief. The modern diet is span-fire new; we've never eaten this way before. (I know it seems like we've always been neck-deep in cereal boxes and partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, but we haven't.) Once you understand this, you'll realize that any comfortable familiarity you may have with processed food is an illusion, because such food has no familiarity with you, with your ancient genome—the real you under the hood.

Download My FREE Ancestral Nutrition Guide: Everything You Need to Know About Real Food on One Page!

Milestones in Modern Metabolism.

Once foods have been highly processed, as most foods in America are, there is no combination of carbohydrates, fats, and protein that will ultimately be healthy. —The Nutritional Therapy Association.

Take a walk with me down memory lane. Let's stroll down the centuries and millennia of eating to an interesting threshold we crossed just 400 years ago. Don't blink; you might miss it:

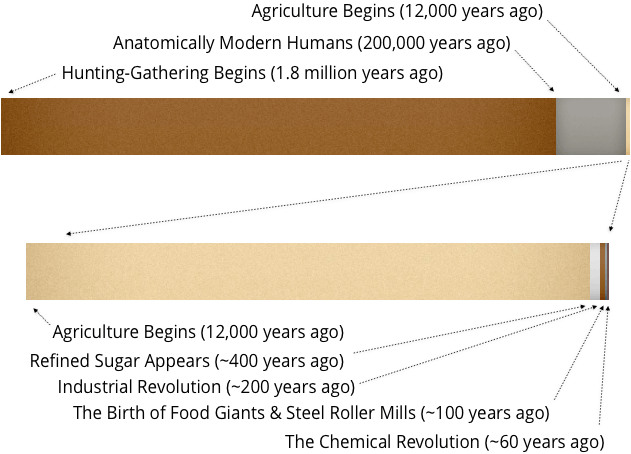

- The Agricultural Revolution: ~12,000 years ago.

- The Introduction of Refined Sugar: ~400 years ago

- The Industrial Revolution: ~200 years ago

- Steel roller mills are invented to atomize grains. Refined flour is born.

- The Birth of Food Giants and Foods of Commerce: ~100 years ago

- Refinements in packaging and shipping allow massive world-wide distribution of sugar and milled-to-death grains.

- Thousands of new shelf-stable foods emerge. Partially hydrogenated vegetable oil (trans fat) is born.

- The Chemical Revolution: ~60 years ago (WWII to The Present)

- Pesticides, Herbicides, Steroids, Antibiotics, Hormones, Additives, Preservatives, Fast Food, GMO all become industrial norms in food production.

- 80,000 novel synthetic compounds are added to the environment in just a few decades.

For a sense of scale, take a look at this graphic:

You may have noticed that this is not a uniform, tick-tock chronology of the last 12,000 years of food production. Instead, it's a long flat expanse, where nothing happens, until bam, we come to the very end and there's this explosion of newness, like an exclamation point. If you were to lay these milestones out on a 12-inch ruler, you would see that the time since the invention of refined sugar till now, takes up less than half an inch. Put another way: if the path to the modern diet were a trip to the moon, you would have to get 96.6% of the way to the lunar surface, before you even caught a glimpse of refined sugar, let alone the introduction of milled-to-death grains, hydrogenated vegetable oils, pesticides, and the rest of it.

Lest you think we can just evolve ourselves to fit the new shiny, consider this: 99% of our genes were formed before the agricultural revolution. That means our metabolism has had about 12,000 years to adapt to farming. Which sounds like a lot. And it is. Yet a sizable percentage of the world's population has, so far, failed to evolve the specific gene sequence necessary to digest something as simple as lactose—lowly lactose: the milk sugar from cows (mostly) that we domesticated some 9,000 to 10,000 years ago!

The gene for "lactase persistence", which enables us to digest lactose as adults, is still somehow missing from 25% of the world's population despite ponderous amounts of time and population mixing. Another 40% to 50% of us can only partially digest lactose as adults. Adaptation is slow business. So I can think of no biologic mechanism—quantum enough, or awesome enough—to keep up with the rate of food novelty now. From an evolutionary standpoint, the modern diet arrives all at once and out of the blue, like an astroid.

When New-Fangled Food Crashed an Ancient Genome: A Case Study.

A sack of white flour. A pound of sugar. As far as our genes know, these products came from outer space. This becomes more clear when we look at examples of native peoples, who have had to adopt the modern diet in a single generation.

In 1991, the New York Times ran a story covering the then curious case of the Pima Indians: a tribe of lean indigenous people, with no history of diabesity before 1940, that had become sick and fat in the evolutionary blink of an eye.

The Pima are native to the deserts of Arizona. Traditionally they ate a diet high in special soluble fibers that form edible gels, gums and mucilages. And they consumed their starches primarily in the form of amylose, a resistant starch, so called because it digests very slowly. In other words, they ate a lot of mesquite meal, cactus, tepary beans, chia seeds, amaranth and acorns. The metabolic effect was striking, almost magical: the Pima enjoyed slow, steady digestion with no wide swings in blood sugar and they reported feeling pleasantly satiated, or full, without any of the berserk cravings that often follow the consumption of processed foods.

It was not to last.

After WWII, the US government decided to help the Pima, by supplying them with refined wheat flour, sugar, coffee, and processed boxed cereals. But these "foods of commerce" behaved like kindling in the metabolic fires of the Pima, flaming up and flaming out so fast, that the eaters began to experience the same kind of blood sugar swings and insulin spikes other Americans had come to think of as "normal".

But it wasn't normal for the Pima. In fact, it was so abnormal, so freakishly new and metabolically disorienting, that they began to develop obesity and diabetes at 15 times the rate of the rest of the US population (itself no paragon of blood sugar control and apparently on a mission to clone Homer Simpson as fast as possible.)

Finally, people started to take notice—and take action.

"When Earl Ray, a Pima Indian who lives near Phoenix, switched to a more traditional native diet of mesquite meal, tepary beans, cholla buds and chaparral tea, he dropped from 239 pounds to less than 150 and brought his severe diabetes under control without medication. In a federally financed study of 11 Indian volunteers predisposed to diabetes, a diet of native foods rich in fiber...kept blood sugar levels on an even keel and increased the effectiveness of insulin. When switched back to a low-fiber "convenience-market diet" containing the same number of calories, the volunteers' blood sugar skyrocketed and their sensitivity to insulin declined." (New York Times, 1991.)

The Times goes on to report the confusion and illness of those Indians who thought they were eating their ancestral diet, but were not, because they had switched to modern varieties of beans and corn with little or none of the nutritive advantages found in the staples of their historic diet. "For example, the sweet corn familiar to Americans contains rapidly digested starches and sugars, which raise sugar levels in the blood, while the hominy-type corn of the traditional Indian diet has little sugar and mostly [resistant] starch that is slowly digested." (New York Times, 1991).

And it wasn't just the corn. The pinto beans that the Federal Government supplied were also more rapidly digested than the tepary beans the Pima had once thrived on. These were, after all, the people who once called themselves "the bean people”—but which beans?

So between the sugar, the flour, the industrial fats, and the shiny new cultivars of corn (and beans?), the Pima found themselves confused and metabolically outgunned. Apparently, eating on the wild side, or on the indigenous side, really matters. Our tongues may like novelty, but our genes appear to distinctly favor their ancestral set points.

Let's take a quick detailed look at the Pima nutrition program, before they encountered the foods of commerce:

Mesquite:

- Mesquite (mes-KEET) produces nutritious pods with a caramel-like sweetness. It's a good source of calcium, manganese, iron and zinc and it contains almost twice as much protein as common legumes. Mesquite's gel-forming fiber, galactomannin gum, is absorbed slowly over a four-to-six hour period leading to smooth blood sugar control (unlike the carbs we typically consume: wheat flour, corn meal, sugar, fruit juice, and soda). The gel has a consistency similar to chia seeds soaked in water. The "Jell-O of the Desert".

- A stand of mesquite can produce as much food through its pods as a comparably sized wheat field. And it can do so without pesticides, fertilizer or irrigation.

Acorns:

- Acorns from the Emory Oak (along with Mesquite pods) are among the 10 best foods ever tested in terms of maintaining stable blood sugar levels.

Amaranth Seeds:,

- Amaranth is a drought-tolerant plant that produces edible seeds and greens. The seeds are high in protein. Both the seeds and greens are high in calcium. When cooked, amaranth has the consistency of couscous.

Chia Seeds:

- Now that chia seeds have achieved superfood status, most of us know what they are. But here's a few things you might not know: they are high in fiber, protein, and omega 3 fatty acids. When mixed with water, the seeds form a gel, making Chia another low-glycemic energy food, another "Jell-O of the Desert". There are stories of Inca runners (royal couriers) holding chia seeds in their mouth, letting them soften and swell, while they ran great distances along mountain routes from village to village, like pony express riders without ponies.

Cactus:

- Buds from the cholla (CHOY-a) cactus are rich in calcium (one tablespoon contains the equivalent of eight ounces of milk). And when it comes to stable blood sugar, both cholla buds and the prickly pear (another Pima favorite) are clear winners.

Tepary Beans:

- Tepary (TEP-a-ree) beans are drought-hardy legumes, once again rich in mucilaginous gel-forming fiber, offering outstanding blood sugar control. Teparies are also a great source of protein, iron, and calcium. They can withstand the 100-plus degrees of the Sonoran Desert, making them the clear ecologic choice for the region.

Of course, the Pima ate other wild foods too, like wild fish and game, which are nutritious and low-glycemic in their own right. But about 70% of their indigenous diet was carbohydrate. What fascinates me then, is the alien character of those carbohydrates: whole, fibrous, and often gel-like—not at all like cereal and soda, nor the rest of our daily carbage.

Looking for a Modern Translation.

The modern diet appears to turn human beings into metabolic misfits, fish out of water.

Unlike fish however, we don't die immediately when we're removed from our ancestral life-support system. Instead, we adapt, or at least we try to, holding ourselves together with bubble gum and bailing wire (modern medicine), while becoming an altogether new creature: a nutritional amphibian, overfed and undernourished.

Maybe it's time to wriggle free, to go back to our origin story and find our nutritional home.

To me, the translation is pretty clear and very close to the Nutritional Therapy Association's ideal of "a properly prepared, nutrient-dense, whole-food diet”—full of fiber, resistant starch, healthy fats, and clean protein—bioindividualized to a person's energy needs and ancestry.

We'll be talking more about what this means in our kitchens and culture in future posts. But before we take that journey, there is one obvious prerequisite: a willingness to cook, or to learn to cook, or to employ a cook, or to marry a cook who wants an adventure. Because, if you stick with me, the age of Top Ramen will be over. Welcome to real food.

Yours in Health and Resilience,

Marc Wagner, MD, MPH, NTP.

P.S. Here's a quick and dirty blood sugar tip I use every morning: Chia-Coconut Fuel. I make it in batches:

- First, I mix 1 tablespoon of chia seeds with 3 tablespoons of coconut oil.

- Then I add 1 tsp of Jem Cinnamon Red Maca Almond Butter.

- I store the mixture in a sealed container at room temperature.

Just before my morning workout, I grab a spoonful and savor it. It provides stable energy for at least sixty minutes of exercise without the discomfort of a pre-workout shake sloshing around in my gut or the energy bonk of up-down blood sugar. (What goes up must come down). I think the Inca trail runners would be proud. Try it and let me know what you think.

What to Read Next: Grow Your Bugs, Not Your Belly.

Cover Photo: "Ride in a Shopping Cart" by Caden Crawford on flickr