Welcome to Your Second Genome.

It isn’t every day that a book offers us a theory of nearly everything wrong with our health—and delivers.

I can’t believe it was only a week ago that Michael Pollan posted a big thumbs up for The Good Gut, by Justin & Erica Sonnenburg, PhDs on his Facebook page. (Liking Pollan’s page has turned out to be one of my better choices in life). I devoured the book. The torrent of ideas and information that spilled from its pages refreshed me and strained me in ways that are hard to describe. When I finally came to the last page, I felt like I had traversed continents, or gotten myself deliciously lost in Lorien for a month—all in the space of a few silvan days.

I love it when a book leaves me feeling dazed and un-confused. That lucid interval between reading the last line and getting up to engage the world again, is something to savor.

With the publication of The Good Gut, the Sonnenburgs have written a tour-de-force book about food and feces, bugs and guts, dirt and diversity, and what it all means for the good life. (And even what it means to be human.) The book brings together years of research and some long-looked-for clarity about why we appear to be getting sicker and sicker in America, despite having the “best” of everything.

Of course, the Sonnenburgs didn’t just wake up one morning and decide to write a best seller about why some of their best friends are germs. Their book is the culmination of a life’s work spent directing their own lab in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford University School of Medicine (as well as directing some real-food-politik at home with their kids).

They’ve made the talk. And they walk the talk.

Why Are We Hearing About This Now?

There are several reasons why this book is important and timely. As Dr. Andrew Weil points out in the Foreword, we are all a little bewildered by the abrupt rise in asthma, allergies, and autoimmunity in the West. And we are positively stumped by the explosion of peanut allergies and gluten sensitivity.

Weil is particularly perplexed by gluten sensitivity (as am I). When you separate the wheat from the chaff, gluten sensitivity still emerges as a growing problem, fad or no fad. How could the staff of life have become such a brutal rod of discipline for so many, so quickly? Weil does not feel the genetics of wheat have changed enough to be the cause of this historic reversal (as some contend). Rather, he agrees with the Sonnenburgs, that rapid alterations in our gut microbiome are to blame.

These alterations stem from four major changes in the way we’ve come to eat and medically treat ourselves over the last 60 years:

-

The widespread adoption of industrialized, processed food, which literally starves our good bugs and feeds our bad bugs.

-

The widespread use of antibiotics, which set the gut flora ablaze and in some cases burn it down altogether—like the poignant passing of an old-growth forest, perhaps never to be the same again. (As in the outer world, so in the inner world: the loss of complex ecosystems has unintended consequences. New and simplified ecosystems may emerge, but they will not necessarily provide the same resilience for the terrain. In this case, the terrain is you). Of course, antibiotics save lives everyday, so we are not going to stop using them. But they will probably not be prescribed casually in the future.

-

The massive rise in Caesarean deliveries, which are sterile and prevent baby from receiving mom's protective microbes in the birth canal.

-

The decline of breast-feeding, which not only further isolates baby from mom’s microbiome, but deprives baby of the zen-belly “fertilizers” in breast milk as well.

When several or all of these insults come together in a single person, it can be a real set up for upset. An ecologic disaster on the inside.

From Zen to Grim.

One of the big ideas in this book is that the microbiome is malleable. For better or worse, it can be changed. It has changed.

That said, it has taken us a long time to connect the dots between the changes in our microbiome and the changes in our collective health. This research is new and subject to continual updates. But the Sonnenburgs are confident enough about the data to say things like:

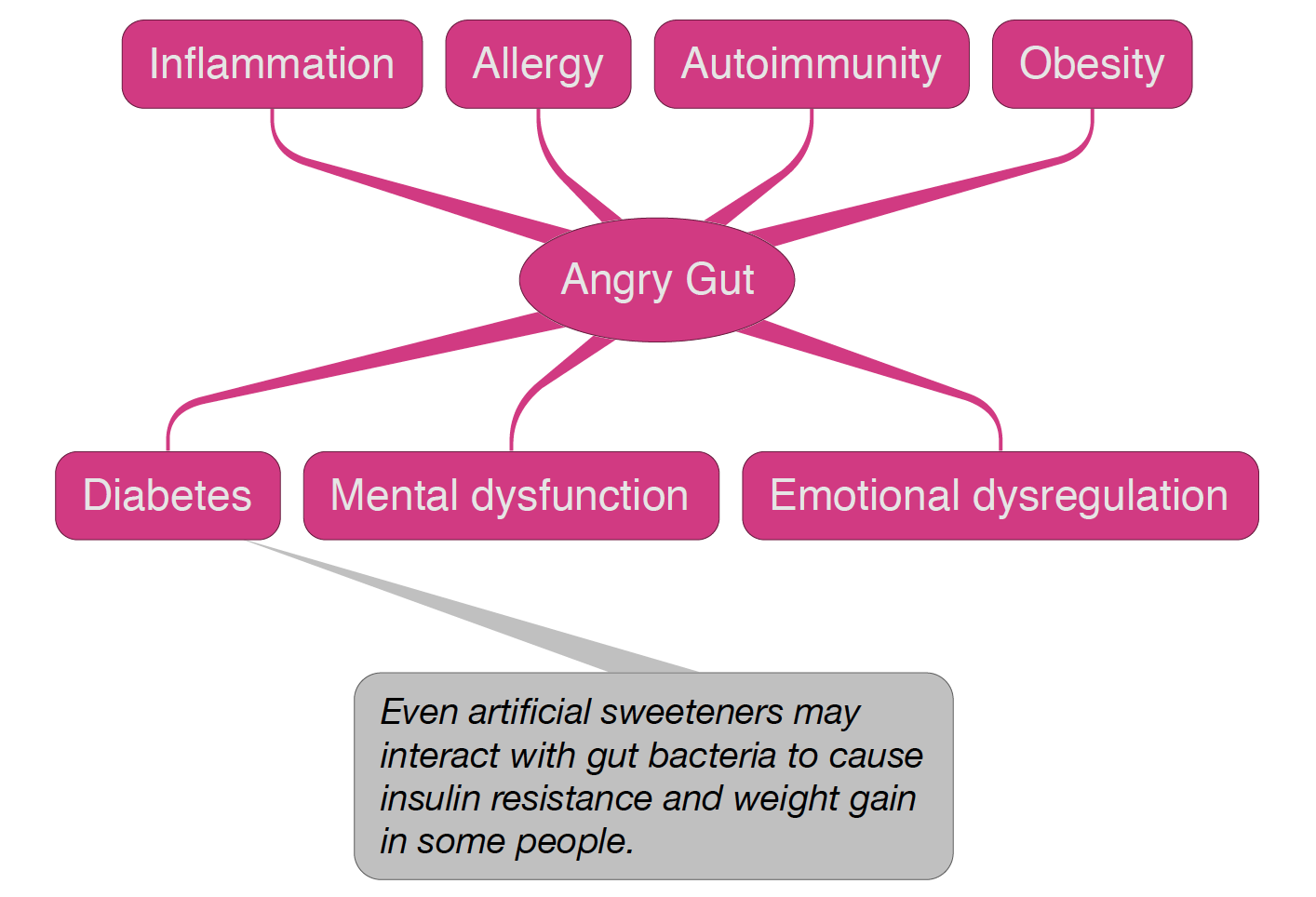

Cancer, diabetes, allergies, asthma, autism, and inflammatory bowel diseases...it is becoming clear that the microbiota plays an important role in the development of each of these conditions.

The way our gut microbiome interacts with our environment is complex. For example, there are counterintuitive things going on all the time, like zero-calorie sweeteners somehow making us fat, not because we use them for fuel, but because our bugs appear to be using them in novel and unexpected ways.

The more out-of-whack our microbiome gets, the sicker we get. This much is clear. But where are we headed? And what exactly can we do about it? These are the questions the book tackles. And tackles rather well, with hope finally coming up in the last two chapters, like a cool breeze.

Nature Is Serious About This.

Regardless of how important we think the microbiome is, or isn't, nature appears to have always thought it was critical. A good example is breast milk. Mother's milk is not just formulated for one little creature, or even two, but for Zillions.

Let me explain.

There are a lot of other mouths to feed besides baby's: "Our gut is home to more than 100 trillion bacteria. If you lined up all of your bacteria end to end, they would reach the moon," says Sonnenburg.

While a baby's gut may not have quite that many critters in the beginning, part of breast milk's job is to coax the growth of more bugs—the right kind of bugs.

The third-most abundant molecule in mother's milk is Human Milk Oligosaccharide, or HMO for short.

HMOs are complex carbohydrates that are so tortuous and spindly they defy any human enzyme to break them down.

So why would mom's body preoccupy itself with making tricked-out molecules that her baby can't even digest? Because there is someone in the gut who can digest them: microbes. And certain microbes need to grow, ASAP, to insure the health of her child.

Every species of mammal produces milk oligosaccharides that are specific to it. HMO's are specific to humans. And they appear to have only one purpose: to shape our "second genome”—our microbiome—as soon as possible after we come into the unsterile world. Not only does this make us more resilient, it is also makes us more human. Because to be human, it turns out, is to be a superorganism—a composite being. We are not only more than the sum of our parts, we are more than the sum of our part's parts.

Our gut is home to more than 100 trillion bacteria. If you lined up all of your bacteria end to end, they would reach the moon.

The idea that your microbiome is your "second genome" is not far fetched. After all, it contains 100x more genes than you do. It's like an enormously complex pet that grows up with you, inside and on you, with more cells, more genetic information, and more chemistry than the rest of your cells combined. The Sonnenburgs call it your personal “bioreactor”—a vast unsupervised laboratory bubbling away, making any number of bioactive compounds that shape who you are. You get a sense of the scale involved, when you realize that there are more microbes living on your hand, than there are people living on the earth.

So, in those first few months after giving birth, mom's body is trying very hard to guide the growth of this new "pet", by offering it designer molecules to feed its most task-oriented bugs, like bifidobacter and bacteroides. (The latter appears to be critical in preparing the infant's gut for the transition to solid food.)

Yeah. I know. Wow.

Conclusion.

As you might expect, The Good Gut begins by shaking us up a bit. And in all fairness, this approach simply recognizes human nature.

For most of us, the microbiome is "out of sight and out of mind”. And even when we see it, we flush it. So it's hard to really care about it. This would be fine, if we weren't at a crossroads in history where "out of site" could mean "out of time":

It is possible that gut bacterial species that make important contributions to our health will become extinct, or so rare that our microbiota won’t resemble that of early humans, and maybe this has already happened to some extent.

Despite this dour prophecy, the Sonnenburgs remain optimistic that we can change our trajectory. Now. In real time. And that it won't take as long as we thought. In babies at least, the microbiome can start changing for the better within just ONE DAY of proper feeding.

And on that note of hope, I'm going to stop.

You have lot’s of questions, I know. So do I. No worries. I’m going to geek out with you on this topic for a few more posts and see how we do.

Till then.

Yours in Health and Resilience,

Marc Wagner, MD, MPH.

P.S. Here's a wonderful animation to help you put everything together, that we've said so far (with a light-hearted twist). Gather the kids around for this one:

Related Posts:

-

Throwing Rotten Tomatoes at Eggs. How alterations in the gut microbiome could turn good food into bad food for some people.

-

Fitting into Your Genes. What happens when genes and environment do not align.

-

Let's Get Started. A primer on Human Flourishing.

-

Grow Your Bugs, Not Your Belly. Does Having a Small Microbiome Give You a Big Gut?

Cover Photo: "Bacteria" by AJ Cann on Flickr