Does Having a Small Microbiome Give You a Big Gut?

When people say "less is more", they generally mean something positive, like less clutter is more freedom, or less agenda is more enjoyment. But in the case of gut microbial diversity, less is just more disturbing.

As if we needed one more thing to add to our waistline woes, research now indicates that a shrinking microbiome may be making us fat.

Once again, we consult The Good Gut, by Justin & Erica Sonnenburg, PhDs

A Museum of Metabolic Syndrome.

I hardly need to point out why the topic of obesity is important. But I will anyway, because the more pervasive a problem is, the more human nature tends to ignore it.

Like bugs collecting on a windshield, the spackle of obesity statistics keeps building up. It’s depressing. We find ourselves squinting past it, so we can just keep driving. And the faster we drive, the worse it gets. There’s no blame in this. It's what humans do when they feel overwhelmed. I don’t like pondering the headlines anymore than you do. I'm grateful for the words of Dr. Christiane Northrup here: "We are responsible to our disease, not for it."

So let's observe our dirty windshield for a minute. Then we’ll consider how we might respond to it.

A quick search of the obesity literature yields a litany of human suffering and grim forecasts: spectacular rises in metabolic syndrome, mushrooming medical costs, childhoods stolen by shame and shortness of breath, a decline in work-force health, slow-motion economic collapse:

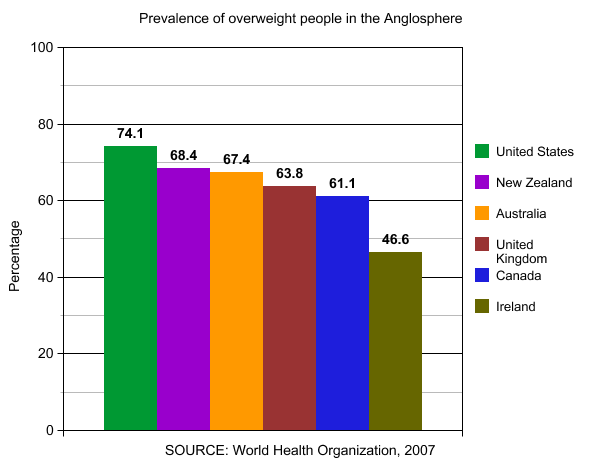

- Two out of every three people in America are considered overweight or obese. That’s 2/3 of the population.

- By 2020, fully 3/4 of the American population is expected to be overweight or obese. (Estimates by The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States has the highest prevalence of overweight adults in the entire Anglosphere.

And here is Animated map of the United States from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showing the rise in obesity from 1985-2010.

Between 1986 and 2000, the prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) quadrupled. Over the same period, extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2) increased by a factor of five.

Between 1963-2002, the prevalence of overweight children tripled.

- Sticker shock: Obesity-realted health care is costing Americans an estimated $117 billion in direct (preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services related to weight) and indirect (absenteeism, loss of future earnings due to premature death) expenses. This exceeds health-care costs associated with either smoking or problem drinking.

- Health authorities anticipate no change in any of these trends.

All of which begs the question:

Are Western democracies, which have made modern history, now in danger of becoming history? It’s no longer hard to imagine a scenario in which, a thousand years from now, our civilization is unearthed and showcased as a cautionary tale: A Museum of Metabolic Syndrome. (Alongside the wind-swept emptiness of Easter Island and haunting effigies of Greenland Norse). Heaven forfend.

What the Heck Is Going On?

The short answer is we don’t know all the reasons why, corpulently speaking, we seem to be stuck in an inflationary universe. But The Good Gut has a few fresh insights that are worth considering.

The most disturbing of these insights comes from the simple observation that animals on antibiotics gain weight—about 15% more weight than animals not on antibiotics.

According to journalist Maryn McKenna (Wired Magazine, Nature, Slate, The Atlantic, and now National Geographic) drug manufacturers first noticed the fat-packing effects of antibiotics all the way back in 1948, when they were looking for new antibiotic markets at the close of WWII—because battlefield medicine was drying up.

At the time, there was no explanation for the phenomenon of antibiotic-associated weight gain. But no explanation was needed for meat and drug producers to see a business opportunity.

And so began the routine practice of feeding antibiotics to animals that are not sick. From the farmers point of view, the benefits are two-fold: not only do antibiotic-fed animals gain more weight, but they can also be crammed into smaller spaces without getting as sick. Voilà. We can squeeze even more fat out of the same square footage without too much animal attrition. Yay, science.

If it weren’t for antibiotics, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) could not exist on the scale they do today.

The difference in antibiotic usage between animals and humans is telling. For example, in 2011The Pugh Charitable Trust noted that 7.7 million pounds of antibiotics were sold to treat sick people. But in the same year, 29.9 million pounds of antibiotics were sold for meat and poultry production—four times as much. That marbled steak in the display case is not just the product of a corn-fed, claustrophobic cow. Antibiotics are playing a role—a calculated one.

So, if we’re successfully fattening animals with antibiotics, could we also be fattening ourselves? The answer appears to be a qualified, yes.

Ground-Breaking Research.

While we still don’t know the exact mechanism behind antibiotics and weight gain, researchers are homing in. And as you can probably guess, it has something to do with the quality and quantity of the bugs in your gut.

According to The Good Gut, studies coming out of Britain now show worrisome trends for childhood obesity related to antibiotic use, particularly in children receiving antibiotics at younger ages, when the microbiome may still be immature and less able to bounce back:

Children receiving antibiotics between the ages of one and two years old were significantly heavier than age-matched controls a full five to six years after treatment.

Studies in mice show the same trend and the Sonnenburgs comment on a possible mechanism:

The antibiotic-treated mice ate the same number of calories as the nontreated mice but were better able to extract and store those calories in the form of added weight. A calorie uptake system that is dependent on the composition of the microbiota would explain the weight gain seen in antibiotic-treated farm animals and may even explain why antibiotic use in children has mirrored rising obesity rates.

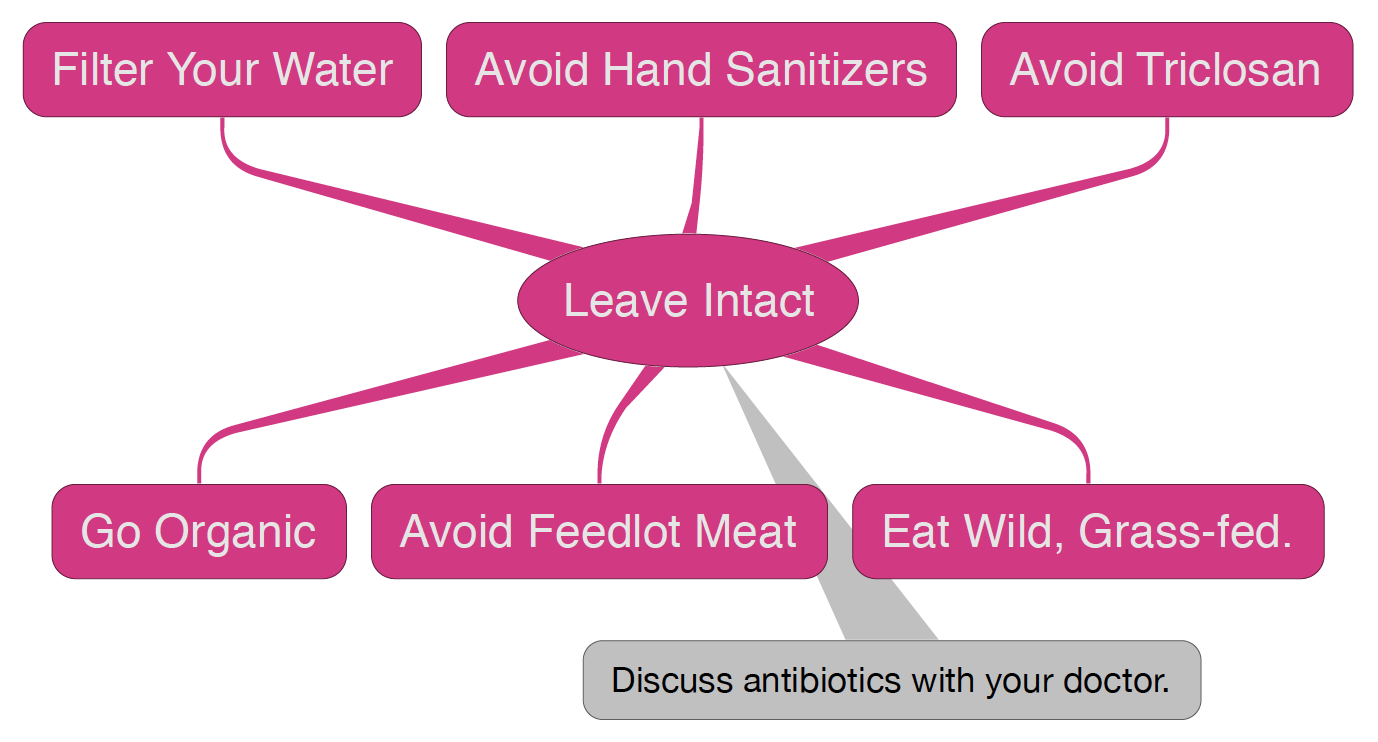

But before you decide to stop taking antibiotics, let me clarify something: Antibiotics are not limited to the prescriptions you get when you’re sick (which you may actually need and should always discuss with your doctor before starting or stopping). There are other antibiotics we routinely overlook, like Triclosan, antimicrobial soaps, hand sanitizers, pesticides, and chlorinated water.

Antibacterial soaps and alcohol-based sanitizers seem to be spreading faster than the germs they are designed to combat, says Sonnenburg.

And there are antibiotic techniques like pasteurization, irradiation, solvents, and sprays that we routinely employ in food production.

And of course, there’s the residual antibiotics in industrial meat itself.

Seventy million people eat at McDonalds every day (National Geographic data). That’s 70 million unprescribed doses of antibiotics daily. Small doses to be sure, but what would “small” mean to a single-celled organism, like our friend Lactobacillus rhamnosus?

The cumulative effect of all these insults is to slowly reduce the complexity of the microbiome around you and in you. So what we’re really talking about here is an antibiotic lifestyle, which includes the entire edifice of food processing, urbanization, and obsessive hygiene that fences in modern life—not just prescription drugs.

This becomes a little clearer in the next study

Out of Africa.

Nearly half the mass of our stool is bacteria. So it's easy to study microbiomes from around the world using stool samples. All you need is a spoonful of poop and you get a universe of bugs.

It’s long been known that rural Africans suffer few, if any, of the typical Western diseases, including obesity. So researchers have naturally been curious about their stool.

Turns out, rural African stool showcases an astonishingly rich and diverse microbiome.

Westerners, by contrast, have a stool microbiome that is impoverished and skewed toward problematic organisms. The homogenous American "melting pot” is not just a social metaphore anymore; it's a biological one.

The Sonnenburgs offer a nice word picture here:

If you think of the microbiota as a jar of jelly beans with the different flavors representing different species of bacteria, the “hunter-gatherer” microbiota is like a jar filled with a complex mixture of many different colors and flavors, some of which are very unusual. The jar representing the Western microbiota has far fewer flavors in a more homogenous or simple mix.

Right. So What does a real hunter-gatherer diet look like then? I want to know.

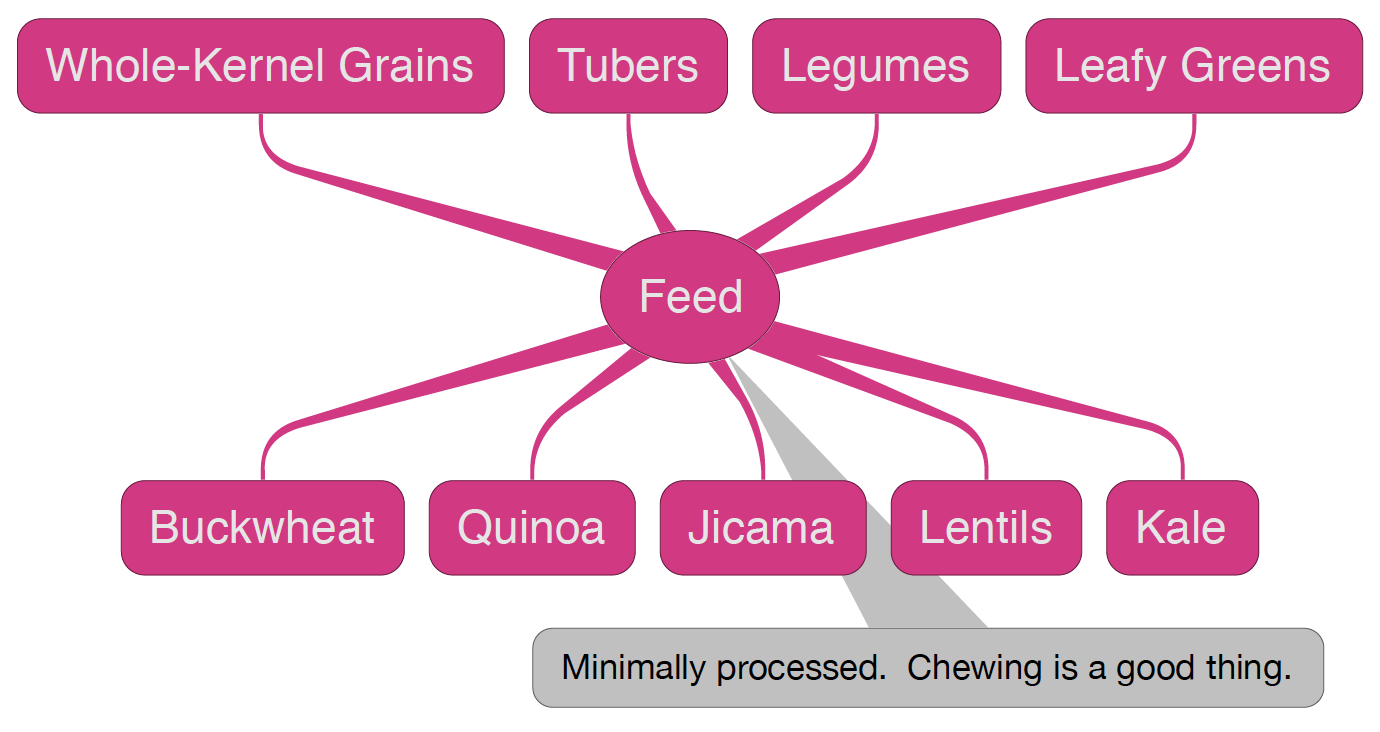

The Hadza consume meat from hunted animals, berries, the fruit and seeds of the baobab tree, honey, and tubers— the underground storage organs of plants. The tubers they eat are so fibrous that after a period of chewing, diners spit out a cud of the toughest fibers.

In fact, the Hadzu eat between 100-150 grams of fiber every day! (That's equivalent to 30 servings of kale, or 25 servings of broccoli, or 10 servings of whole-kernel Quinoa, or 6 servings of whole-kernel buckwheat, or 3.5 servings of Jicama). Yet the average Westerner eats only 10-15 grams of fiber, and not every day.

I remember when I first encountered The Paleo Diet here in the United States. I got the impression that meat was the main event. But the ancestral diet pictured here, while certainly not vegan, involves an incredible amount of chewing, chewing, chewing, chewing—on plant fiber.

So Tell Me, What's Your F/B Ratio?

Dr. David Perlmutter unpacks the fiber-microbiome connection even more in his new book, Brain Maker

According to Perlmutter, one striking feature of the Western microbiome is the ratio between two main groups of bacteria: Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (hence, the "F/B" ratio).

In general, Westerners tend to have high F/B ratios (Firmicutes dominate). But the opposite is true for rural Africans whose ratio favors the Bacteroidetes, especially Provetella Bacteroidetes.

This makes sense when you realize that Provetella are really good at digesting plant fiber for their own purposes and then producing beneficial byproducts for us in return—like short-chain fatty acids that directly nourish the lining of our gut, helping us maintain a healthy barrier there. Provetella grow well in the guts of low-tech rural tribes who eat large amounts of fiber. But they starve to death in the guts of Americans and Europeans, whose diets are low in fiber.

And the Firmicutes? What are they doing?

Firmicutes seem to be really good at squeezing every last calorie out of your food and then passing the calories directly on to you. They may even produce chemical messengers that tell your body to store calories. This could be useful in a famine, but under a prevailing dietary wind of sugar and processed food, Firmicutes grow out of control, right along with their host.

Currently we don't know what the optimal F/B ratio is, but we can say this: What we thought was "normal" gut flora in the West, probably isn't normal at all compared with what has been normal for humans throughout most of history.

If rural Africans are any guide, our ancient genome appears to feel most at home, when it is snugly matched with its ancient microbiome.

No Poop for You.

Okay. Here we go. The re-poopulation studies. Yes, it's true. Researchers have induced obesity in mice by performing poop transplants.

Like humans, obese mice have different microbiomes from skinny mice. And, by transplanting one microbiome to the other, scientists have produced startling effects, as noted in The Good Gut:

Jeff’s team transplanted the microbiota from the obese mice into lean mice with no previous microbiota. Suddenly the lean mice with the obese microbiota began to gain weight, even though there had been no change in their diet or exercise habits! What these scientists had shown, to the surprise of many, was that the gut microbiota is enough to cause weight gain in an otherwise lean, healthy mouse.

These poop transplants appear to work in the opposite direction too--with one caveat. Fat mice can become thin when they get "a donation" from their skinny friends, but only if they change their diet afterward to nourish the new microbes (otherwise, the fat bugs continue their feeding frenzy and the skinny bugs never really get a place at the table).

I probably don't need to tell you, but don't try this at home with your skinny friends. Fecal transplants have to be vetted for disease risk and viability before they can even be used and the procedure itself must be performed by a doctor.

Currently, the FDA strictly regulates fecal transplants. They are approved only for the treatment of life-threatening C-difficle infection (for which they are 90% effective).

However, other countries are making more liberal use of fecal transplants. Someday we may see additional approvals in this country for obesity, autoimmune disease, and even autism. In the meantime, the FDA appears content to wait and let the rest of the world experiment on itself.

Summary and Suggestions.

Okay. Let's review what we've learned and then see if there is anything practical we can do to grow better bugs instead of bigger bellies.

First, review:

- Less microbial diversity is associated with more obesity.

- Antibiotics not only fatten animals, but appear to fatten humans as well through a mechanism involving loss of microbial diversity.

- A hyper-hygienic lifestyle, including chemically altered food and water, probably contributes to gut flora disruption quite apart from prescription drugs.

- Obesity appears to be linked not only to a loss of gut microbial diversity but to a loss of balance between two bacterial phyla in the gut as well, Firmicutes and Bateroidites. Dietary fiber plays an indispensable role in maintaining both gut microbial diversity and favorable ratios among microbes.

- The results of fecal transplants in mice strongly support the hypothesis of microbiome-mediated obesity.

While these data are new, the Sonnenburgs think it's reasonable to take safe actions now, instead of waiting ten years before everything is figured out:

Within our own family, we have used our knowledge of the microbiota to make some big changes in how we live. Lessons from our lab and those of other microbiota scientists around the world have guided how we eat, what we pack in our kids’ school lunches, how we clean our house, and how we spend our free time.

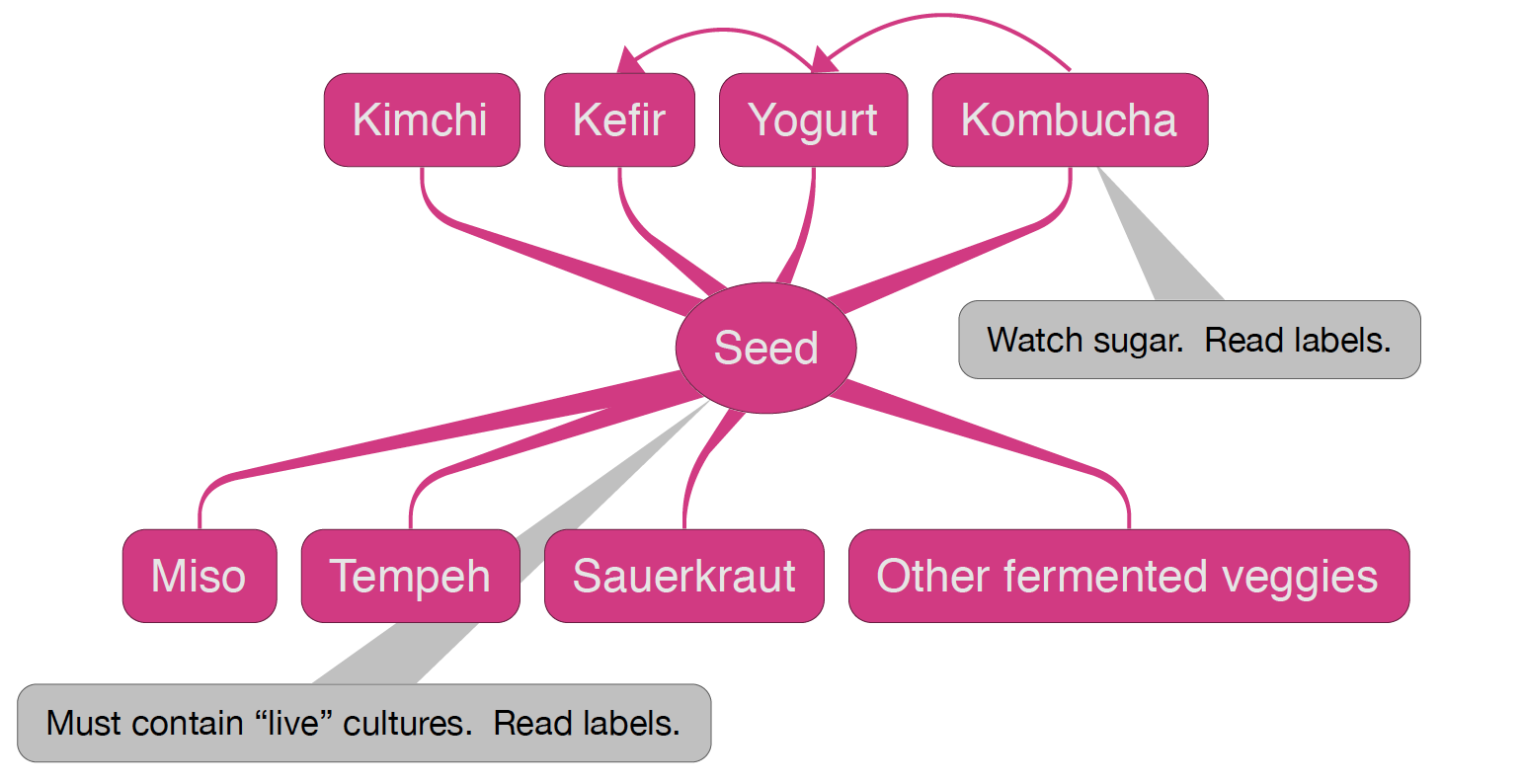

The Sonnenburgs do a number of things. I won’t go through them all here but their efforts seem to fall into three broad categories. I've labeled them Seed, Feed, and Leave, to help me remember them:

Seed the microbiome with fermented foods: The Sonnenburgs enjoy a lot of traditional fermented foods like kimchi, sauerkraut, miso, tempeh, unsweetened yogurt & kefir, and low-sugar kombucha (I personally drink Kombucha with no more than 2 grams of sugar per serving). They also routinely get their hands dirty in an organic garden, which is rich in soil microbes. And they have a dog that liberally shares its own diverse microbiome with the household.

Feed the microbiome with prebiotic foods (high-fiber, low-sugar, low-starch): The Sonnenburgs have made a real attempt to go off the processed food grid and to eat genuinely whole-kernel grains, roots, tubers, leaves and other fibrous plant foods that feed the microbiome and help it diversify.

Leave the microbiome intact (as best you can): The Sonneburgs avoid hand sanitizers. They reserve aggressive hand washing for flu season and public events; they filter their water to remove chlorine; they eat only pasture-raised meats and wild fish (and not too much); they eat organic; and they discuss antibiotics with their doctor to find alternatives when appropriate.

So the authors of The Good Gut have outlined a good place to start for individuals and families who are already healthy and want to stay that way. It's possible that more aggressive approaches to gut healing, like the 4R Program, may be necessary for some individuals. In any case, always clear these changes with your doctor first, to assess for a good fit with your unique health conditions.

In the future, we may be able to repoopulate ourselves with crapsules from pristine donors in rural Africa. But until then, we'll have to do the best we can, which is certainly better than we are doing now. Perhaps we can even avoid embarrassing hi-tech solutions by taking a page (instead of a poop) from primitive cultures and lifestyling our way back to a better microbiome from scratch.

On that note, I'll leave you with C.S. Lewis:

We all want progress, but if you're on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive.

Yours in Health and Resilience,

Marc Wagner, MD, MPH.

Related Posts:

- The Good Gut. Welcome to Your Second Genome.

- Carbs: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. It's not about getting a carbohydrate divorce; it's about changing your carbohydrate source.